By Hasnain Gardezi (APP)

Every summer, as the subcontinent bakes under the unforgiving sun, something quietly ripens in its orchards. From the hot, humid fields of Sindh and Malihabad to the coastal valleys of Ratnagiri, the mango, known as the King of Fruits, returns with its golden glow, sweetening both palates and hearts.

Beyond being merely a seasonal delicacy, the mango has long played a refined and surprising role. It speaks when politics fall silent, serves as a humble diplomat in straw-lined crates, and acts as a golden ambassador that revives strained relations while sweetening those already strong.

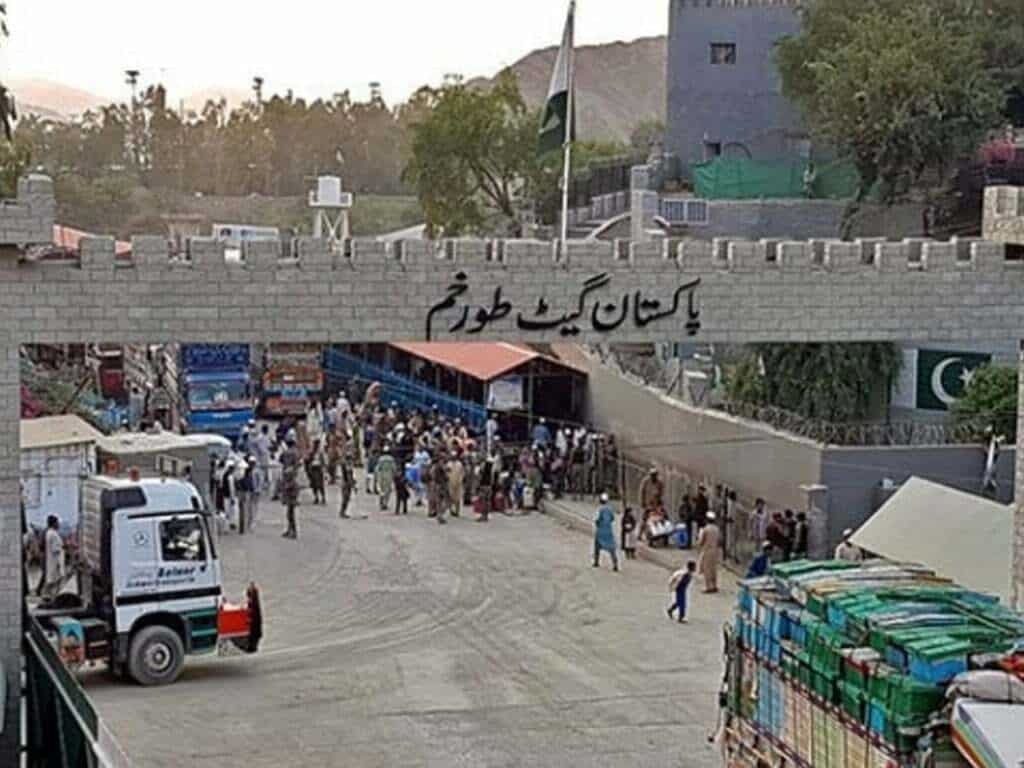

Each year, with the arrival of the monsoon season (Sawan), mango crates begin their quiet journey, not just to markets but also to embassies, foreign ministries, presidential residences, and the homes of friends and families across borders. Often, these gifts are more than mere tokens; they are deeply symbolic gestures, fragrant peace offerings wrapped in jute and tradition.

Mango (King of fruits) (diplomacy is not a new concept; it has shaped soft power exchanges for decades across South Asia and beyond. For instance, in 1955, during the Cold War era, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru sent crates of Alphonso mangoes to Soviet leaders in a subtle bid to strengthen ties with Moscow. In 1968, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Mian Arshad Hussain presented a crate of Sindhri mangoes to Chairman Mao Zedong. This gift sparked China’s now-famous Mango Cult, with the fruit becoming a symbol of Mao’s connection to the working class during the Cultural Revolution. In 1981, amid high tension with India, Pakistan’s President Zia-ul-Haq sent crates of Anwar Ratol mangoes to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Although a small gesture, it was widely reported as an attempt to thaw diplomatic frost. More recently, in 2022, Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina dispatched one metric ton of Amrapali mangoes to Indian leaders, including President Ram Nath Kovind and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, reinforcing regional friendship through fruit.

Read also: Abazai Mango of Charsadda: Pakistan’s rare and naturally sweet Mango variety

Believed to have been cultivated in South Asia for over 4,000 years, the mango has travelled through ancient trade routes and empires, from Buddhist monks planting groves in the 4th century BCE to Mughal emperors breeding royal varieties in their palace gardens. Today, it is a shared heritage fruit among countries that often find little else in common.

For millions across the subcontinent, the mango is not just a fruit; it’s a season, a memory, and a shared joy. It evokes long, sticky summers, mango juice dripping down chins, school holidays, and monsoon meals. To give a mango is to share something sacred—family, identity, and abundance. In every bite lies something ancestral.

Beyond diplomacy and culture, the mango is a nutritional powerhouse, rich in Vitamin C that boosts immunity, Vitamin A that supports skin and eye health, and antioxidants and fibre that aid digestion and fight inflammation. Just one cup of mango provides nearly 70% of the daily Vitamin C requirement, making it as beneficial for your health as it is delightful for your palate.

Mangoes come in hundreds of varieties worldwide, each with its fan base. The top five mango varieties loved around the world include Alphonso from India, known for its saffron color, silky texture, and sweet aroma; Sindhri from Pakistan, a large and juicy favorite that arrives early in the season; Nam Dok Mai from Thailand, slender, golden, and intensely aromatic; Keitt from Egypt and the USA, green-skinned, tangy-sweet, and fiberless; and Miyazaki from Japan, deep red, incredibly sweet, and extremely rare. At the luxury end of the market, Japan’s Miyazaki mangoes are the most expensive in the world, selling for up to $4,000 per pair. Cultivated under precise conditions, they are regarded as more of a luxury statement than just a fruit.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the five biggest mango-producing countries are India, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Together, they account for over 75% of the world’s mango supply.

While policies may freeze and borders may close, the mango continues to quietly cross them, wrapped in straw, kissed by the sun, and welcomed with open arms. As the world navigates rising nationalism and fragile diplomacy, the mango serves as a reminder that sometimes sweetness can achieve what strategy cannot. In the stormy theatre of politics, it remains the softest and most delicious diplomat we’ve ever known.